Sterilization of medical supplies

Consultancy, training, publications, research. With focus on developing world

At the Wageningen University here in the Netherlands within the context of the study on Health and Society, the topic Global Health is presented.

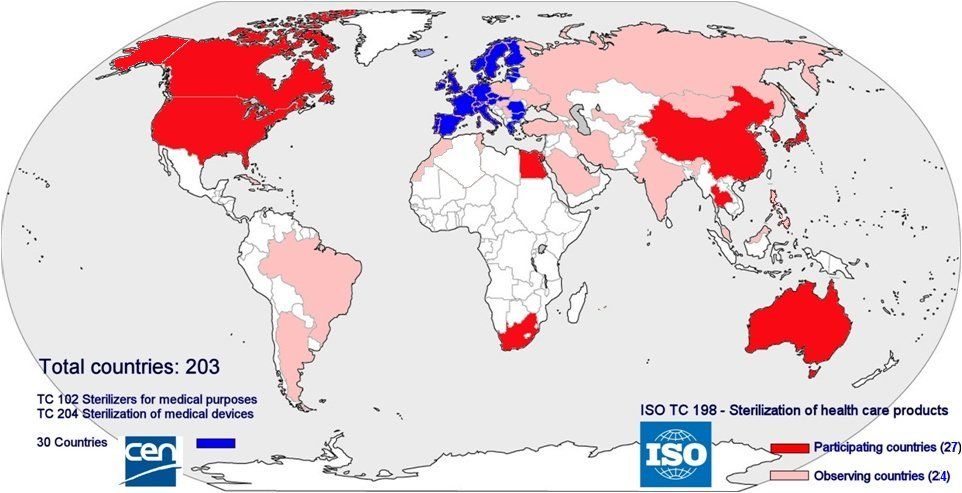

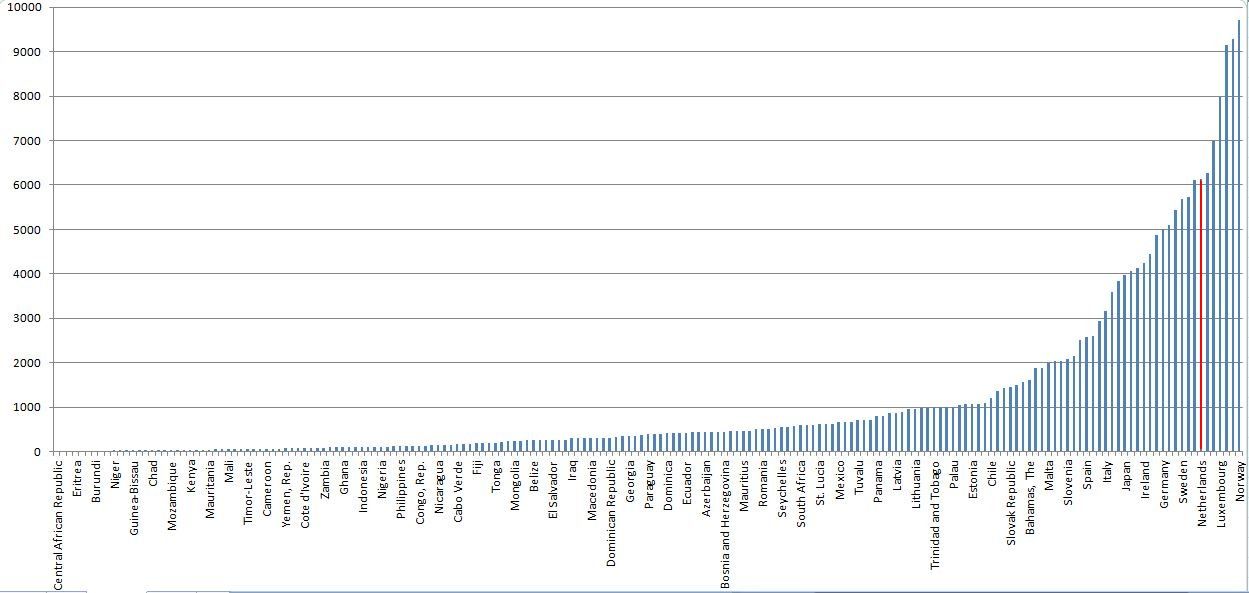

For this topic Jan was invited to present on his experiences in the developing world with focus on the problems that are caused by the International Standards for technology in the healthcare system. Title of the lecture: Facing the standards gap. Using Sterilization as field of experience, he described a range of cases as he met in several African countries. With non-functioning sterilizers caused by non compatibility of standards with the local socio-economic reality. The main conclusion was that the majority of standards are developed in a context of the industrialized world, where the infrastructure is available to meet the requirements as described in the standards. Of the African continent on 3 countries are member of the ISO technical commitee for sterilization. Thus specific problems met in these countries are not reflected anyin any way in the text of the standards. Thus there is a big gap between the reality in many countries and the reality that is assumed when implenting the standards as they have been formulated. A statistic of the amount of money available for health care per capita per year, as made available through the WHO, shows a clear factor in the reason behind the problem. Societies with less than 100 USD/per person per year as compared to the 1000 and more in the industrialied world clearly demonstrate the root of the problem. Transplanting technology developed in that context to a country where that infrastructure in not available is bound to fail. During the lecture guidelines were proposed for addressing the issue. It will be great challenge to handle this issue, that has enormous effects on the health of millions of people world wide.

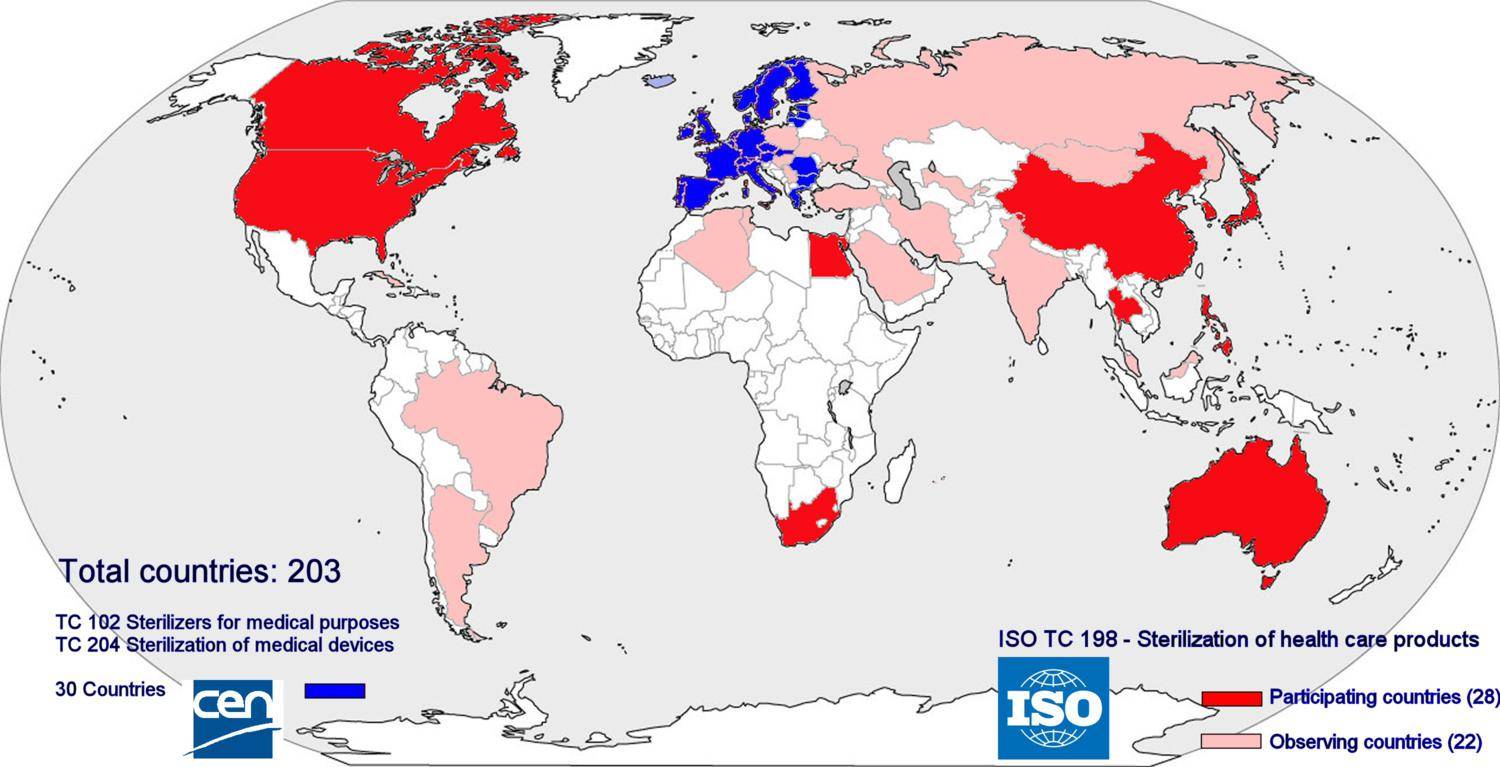

2016: Member countries of CEN and ISO Technical Committees on sterilization. ISOTC198; CENTC192T; C204 Sterilization

The presentation can be viewed here.

The lecture as based on an article that was published in the scientific Journal Zentral Sterilization/Central Service: 2014-3; Facing the standards gap: a sterilizer for the rest of us.

The first edition of the book, was published in 1996 with approval of the then ESH (European Society for Hospitals Sterile Supply). It was in the English language and publication was through HEART Consultancy itself. Since that time it has been published into a wide range of languages. In several countries it has become the official textbook for training of staff in the CSSD. The various editions have been edited and verified with sterilization associations and companies in the respective country. The editions are available through the respective publisher. By clicking on the image of the book or the language name you will get more detailed information of the selected book.

At the moment the Chinese version is yet being compiled. It is expected to be published by the end of 2024

Notice: On 25-11-2023 Jan has transferred the copyright of his books and eLearning to the Sterilization Association of the Netherlands (SVN). For information on the various edtions please contact SVN. E-mail: info@sterilisatievereniging.nl

| Language | Cover | ISBN/Title | Edition | Year | In collaboration with; Publisher |

| English |

|

978-3-88681-189-2 Cleaning, Disinfection and Sterilization of Medical Supplies. Special 4th English edition for SteelcoBelimed |

4 | 2025 | SteelcoBelimed, Italy Published through MHP-Verlag The book is for internal use at the SteelcoBelimed Academy and SteelcoBelimed clients. For obtaining a copy, please contact your SteelcoBelimed representative |

Nederlands |

|

978-90-9038729-1 Sterilisatie van medische hulpmiddelen met Stoom. 5e herziene druk. |

5 | 2024 | Sterilisatievereniging Nederland (SVN) Printed through: Karstens Mediamakers, The Netherlands |

Spanish Español |

|

978-3-88681-184-7 Limpieza, Desinfección y Esterilización de Productos Sanitarios |

3 (eBook) | 2022 | Antonio Matachana, S.A. You can order the book at: MHP Verlag, Germany |

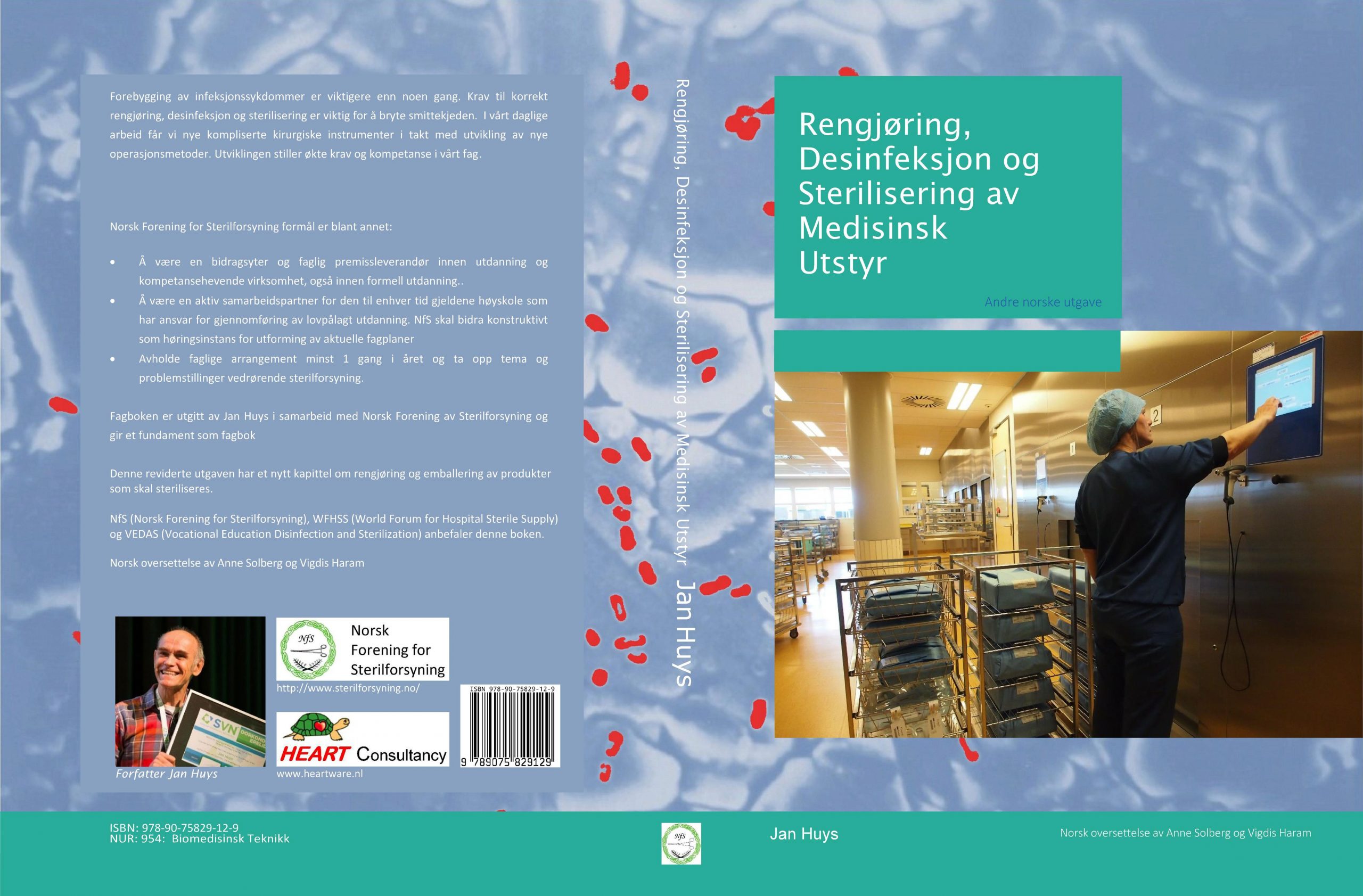

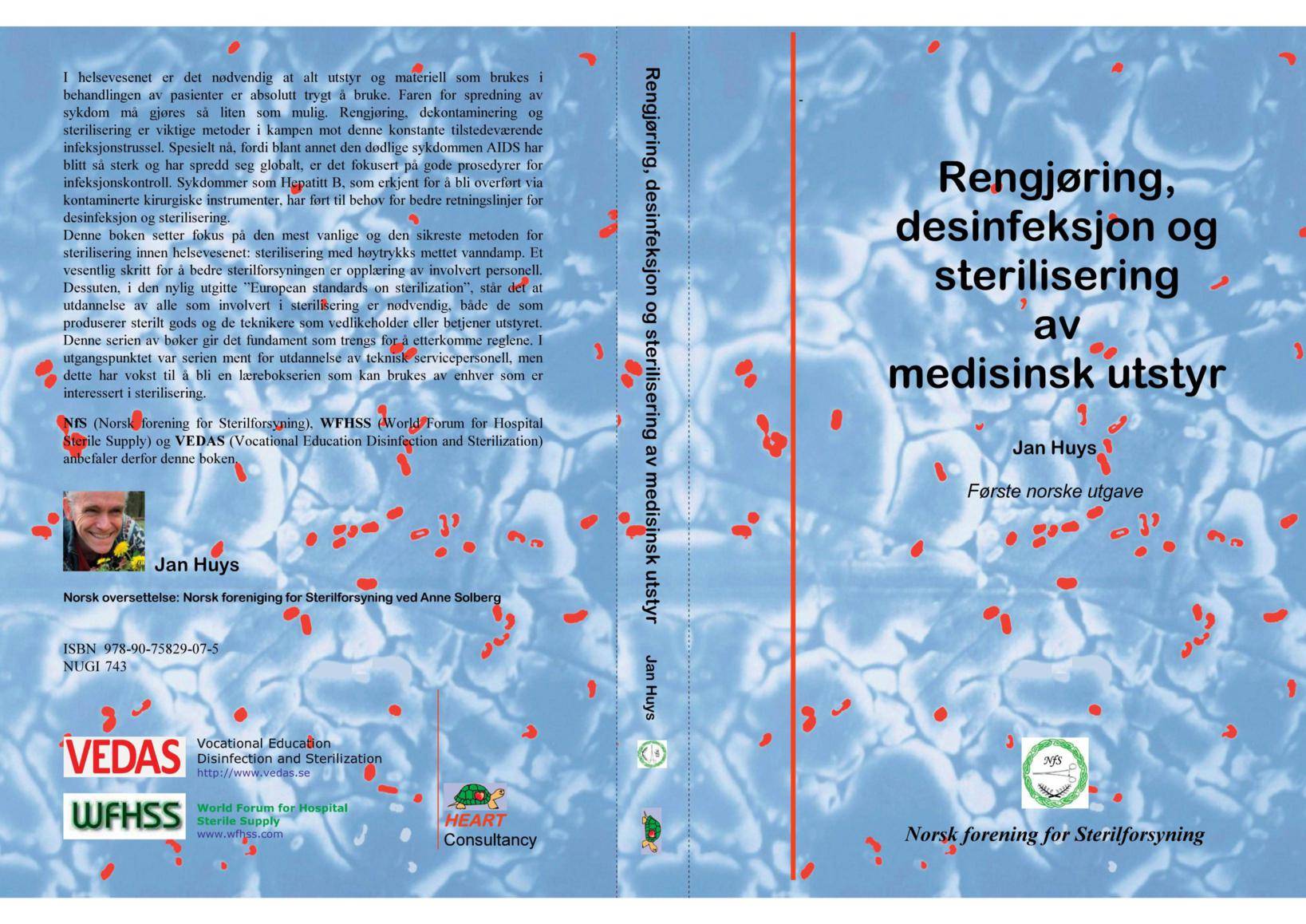

Norsk |

|

978-90-75829-12-9 Rengjøring, Desinfeksjon og Sterilisering av Medisinsk Utshttp://www.sterilforsyning.no/tyr |

2 | 2022 | NFS, Norsk Forening for Sterilforsyning You can order the book at the Webshop of NFS |

Latvian Latviski |

|

Medicīnisko ierīču sterilizācija piesātinātā ūdens tvaikā | 1 | 2021 | Sterivita/IKSA. Infekciju Kontroles un Sterilizācijas Asociācijā http://www.Sterivita.lv You can order the book at: Arbor, Lv |

Svenska |

|

978-90-75829-10-5 Rengöring, desinfektion och sterilisering av medicintekniska produkter |

1 | 2021 | Steriltekniska Föreningen. Swedish translation by Birte Nielsen Oskarsson of the Skånes Universitetssjukhus Malmö, Sweden. You can order the book at: Steriltekniska Föreningen. |

Nederlands |

|

978-90-75829-09-9 Sterilisatie van medische hulpmiddelen met stoom. 4e druk |

4 | 2021 | SVN, Sterilisatie Vereniging Nederland. Interster International, Wormerveer, Netherlands |

|

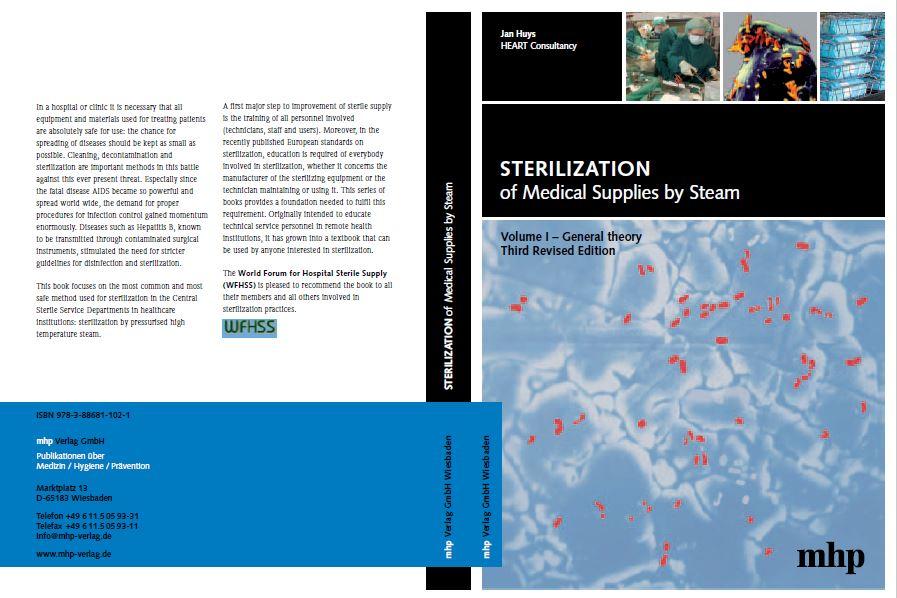

978-38-8681-102-1 Sterilization of Medical Supplies by Steam |

3 | 2010 | WFHSS, World Federation for Sterilization Sciences. MHP Verlag, Germany |

|

Nederlands |

|

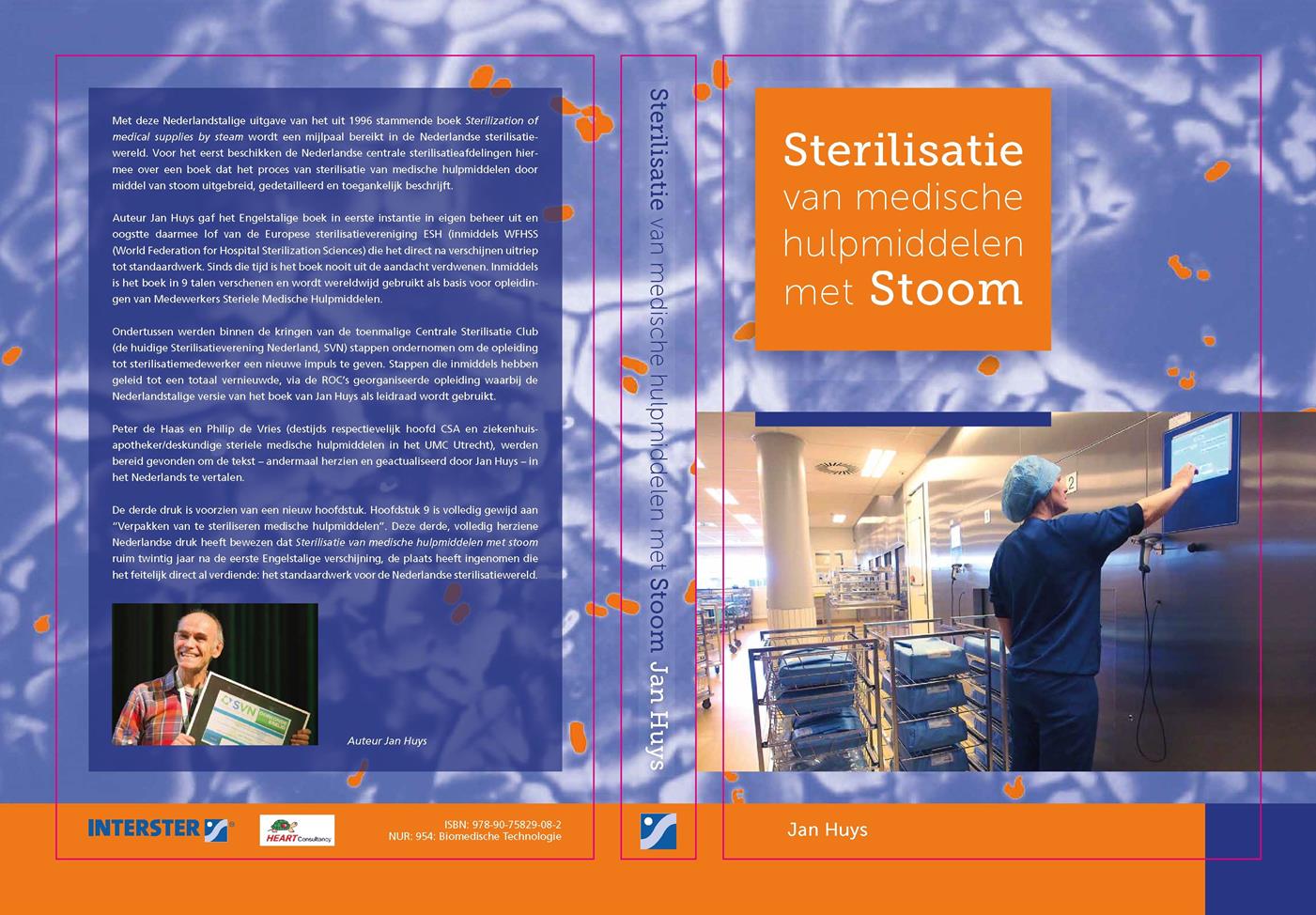

978-90-75829-08-2 Sterilisatie van medische hulpmiddelen met stoom. 3e druk Uitverkocht |

3 | 2018 | SVN, Sterilisatie Vereniging Nederland. Interster International, Wormerveer, Netherlands |

Nederlands |

|

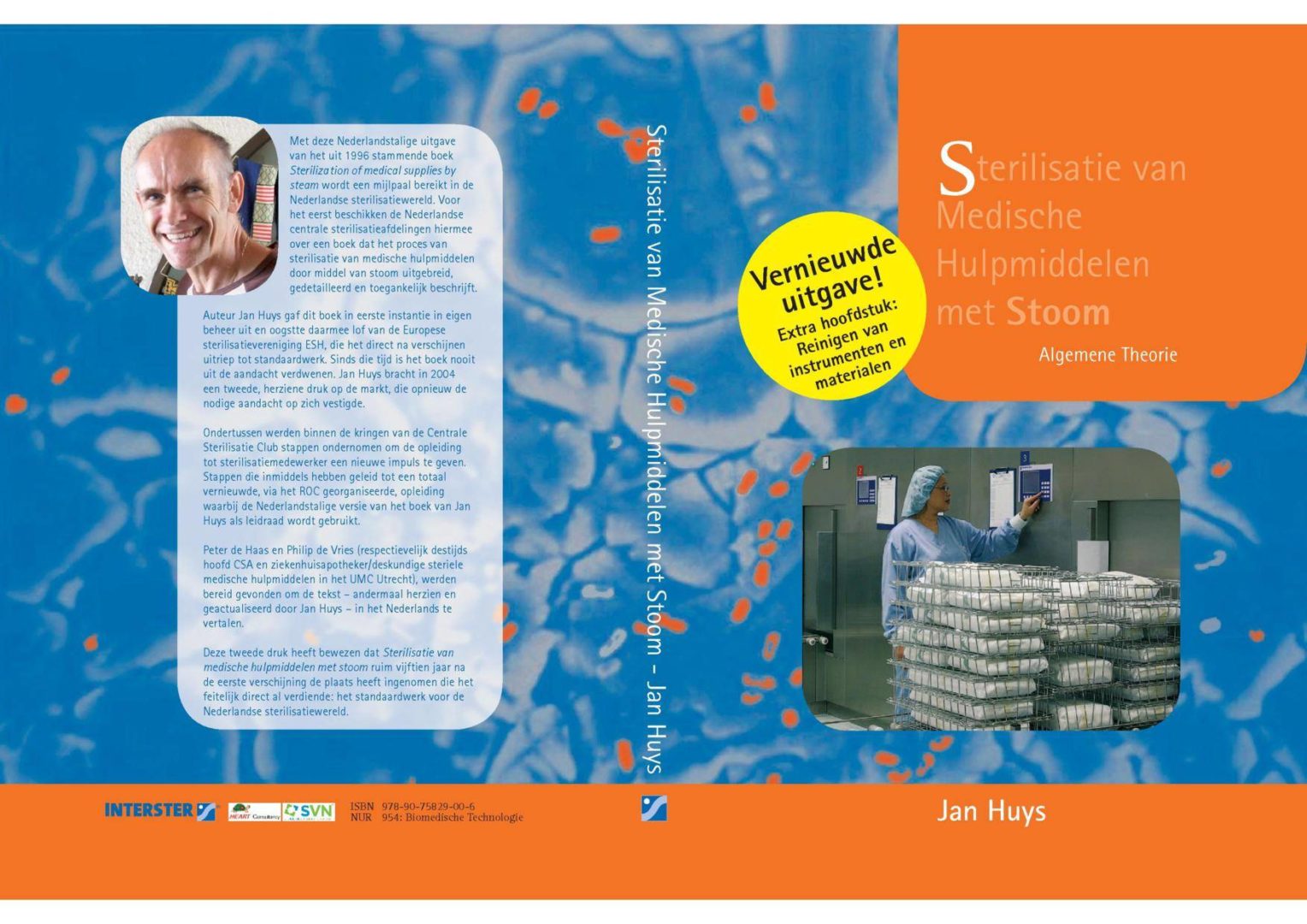

978-90-75829-05-1 Sterilisatie van medische hulpmiddelen met stoom Uitverkocht |

2a | 2014 | SVN, Sterilisatie Vereniging Nederland. Interster International, Wormerveer, Netherlands |

Français |

|

978-38-8681-139-7 Stérilisation des dispositifs médicaux par la vapeur. |

2 | 2016 | SF2Société Française des Sciences en Stérilisation MHP-Verlag, Germany |

Español |

|

90-75829-03-5 Esterilización de Productos Sanitarios |

2 | 2016 | Antonio Matachana, S.A. MHP Verlag, Germany |

ру́сский язы́к |

|

978-3-88681-110-6 Стерилизация паром медицинских изделий Общая теория |

1 | 2013 | DGM ФАРМА АППАРАТЕ РУС Moscow. MHP Verlag, Germany |

Polski |

|

978-83-932434-02 Sterylizacja ZasobówMedycznych |

1 | 2011 | PSRSDM, Polskie Stowarzyszenie Rozwoju Sterylizacji i Dezynfekcji Medycznej |

Norsk |

|

978-90-75829-07-5 Rengjøring, desinfeksjon og sterilisering av medisinsk utstyr Out of print |

1 | 2014 | NFS, Norsk Forening for Sterilforsyning NFS, Norsk Forening for Sterilforsyning |

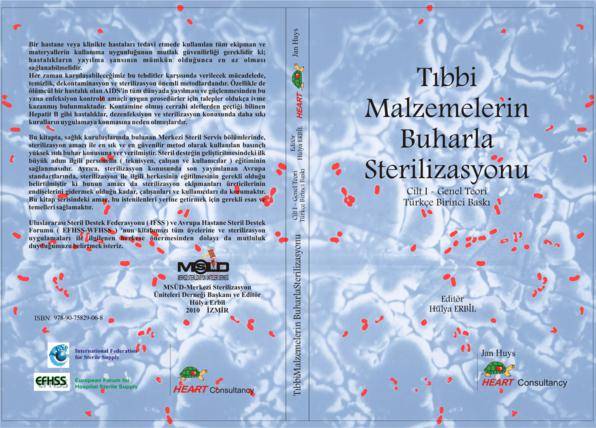

Türkçe |

|

90-75829-04-3 Týbbi Malzemelerin Buharla Sterilizasyonu |

1 | 2010 | MSUD, Merkezi Sterilizasyon Üniteleri Derneği MSUD |

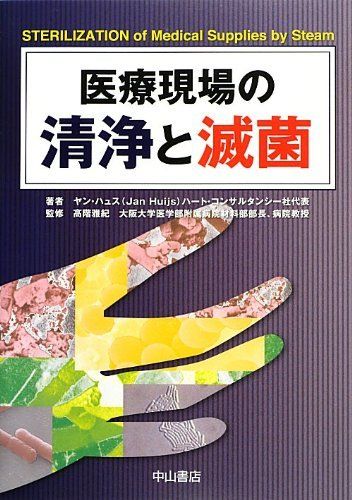

| Japanese 日本語 |

|

978-4521736730 医療現場の清浄と滅菌 |

1 | 2012 | Meilleur Co., Ltd. ミュール株式会社中山書店 Nakayama publishers, Tokyo, Japan |

Training is crucial for reducing the gap between nations

By Jan Huijs – HEART Consultancy, The Netherlands. jh@heartware.nl

The international standards for sterile supply are embedded in Western societies; their implementation requires a strong economy. However due to many socio-economic limitations, transferring these standards – and the resulting advanced technology – to low-income countries is bound to fail. Manufactures are forced to comply with the standards and as a consequence appropriate sterilization equipment and related supplies for this market is hardly available anymore. A major problem is caused by the by the way the requirements for validation of processes have been defined. The current situation related to autoclaves (sterilizers using steam as sterilizing agent) in target health facilities was analyzed; followed by research and development and resulted in prototypes that eventually should mature to an adequate autoclave for the rest of us.

Many health facilities have to operate under harsh conditions with poor and/or limited water supply; poor/limited or even no electricity supply; and often long distances over a very poor road network. Well trained staff is extremely scarce and companies available may be very expensive, especially for a remote hospital that may be hundreds to a thousand of kilometers away from the capital, making only the trip of the technician to come to the site already a financial challenge for the hospital.

The difference between the average spending on health care per person of a population in high income and low income countries is huge. For example in the United States this spending may be approx USD 8200 per person pear year, whereas in Malawi it is as little as approx USD 74 [2]. A difference of a factor 110! It is obvious that technology developed in high income society, assumes the infrastructure of such society: The technology and the resulting products are embedded in their society. And usually requires the infrastructure and related financial resources to keep them operational. The incredible big gap of financial resources and all its implications makes it obvious that advanced equipment developed to be used in the industrialized world is bound to fail when taken to a society where only a fraction of the financial resources are available.

WHO: 2013; Country’s per capita spending on healthcare

2009-11-14: New autoclave donated by the French Embassy; never used. Bangui, CAR. No further technical support nor adequate training was provided. Reason of malfunctioning: lack of training; no compressor for pneumatic valves was supplied.

Africa is undergoing a communications revolution. Mobile phones have become accessible to major parts of the populations. Mobile phones are very high tech devices; which in spite of that are a huge success in also remote African settings. Whereas advanced autoclaves are found broken down and not used in many places. A major reason here are the economy of scale and the cost per item. Mobile phones are used by the tens of thousands. For such quantities it is economically viable to set up an infrastructure to have the network and the equipment operational. Moreover the price is relatively low and thus are affordable for most individuals. In addition the telephone has a tremendous positive impact on virtually everybody’s life. Autoclaves however are only used in health facilities; thus quantities are very low; while the diversity of makes and models is huge. Of some make/model there may be only a single unit in the country. This makes it for a manufacturer/supplier economically not viable to set up a service network. It simply is too expensive. Thus, there is no or virtually no support for the ever more complex equipment, resulting in many broken down machines. In addition the requirements for utilities such as water and electricity has become more stringent making the equipment even more vulnerable for breakdowns.

As for may other fields of industry and services, a wide range of standards related sterile supply have been compiled. Main objectives are to assure safety and health of users and patients, to provide a minimum level of quality and to facilitate international trade. In Europe the standards are issued and managed by CEN (Committée Européenne de Normalisation) whereas ISO (International Standards Organization) compiles standards that are to be worldwide. Compliance with standards is voluntary; however meeting the requirements of standards can be used to demonstrate compliance with the relevant legislation; in the European Union this is the Medical Device Directive. In the context of the Medical Device Directive sterilizers are medical devices and thus sterilizers must comply with the directive. In order to complement the European legislation, governments may have additional national laws. Due to several (mostly economical) reasons, the target countries in the developing world however are not or cannot be members in these committees. Sub-Saharan Africa has not a single member. Therefore the specific problems related to these countries are not considered in the formulation of the standards. The content of the standards is based on the assumption that they are implemented in the member countries. The standards thus are embedded in the richer, Western societies in which the often totally different conditions of the non-member countries are not considered.

Membership of ISO and CEN. No low income countries are member of the Technical Committees (TC) related to sterilization in the standards organizations and thus have no influence on the standards that are formulated

Membership of ISO and CEN. No low income countries are member of the Technical Committees (TC) related to sterilization in the standards organizations and thus have no influence on the standards that are formulatedIt is a requirement of the standards on sterilizers that of any autoclave its processes are validated. This implies that there is to be documented evidence that the autoclave renders sterile products and that the process is reproducible. In this context human actions are not considered reproducible and thus also manual control of a machine is not reproducible. In the sequencing of a process, wherever possible, the human factor must be excluded. However, when I, together with many other people board a bus, I put my life in the hands of the bus driver. His actions cannot be validated. We rely on him. The responsibility of the bus driver is not less then a person operating a sterilizer. But still busses are manually driven. And is accepted everywhere. Why then not, at least in locations where advanced technology is not feasible, accepting manual control for sterilizers by well trained operators using reliable autoclaves that result in adequate sterile goods when operated well?

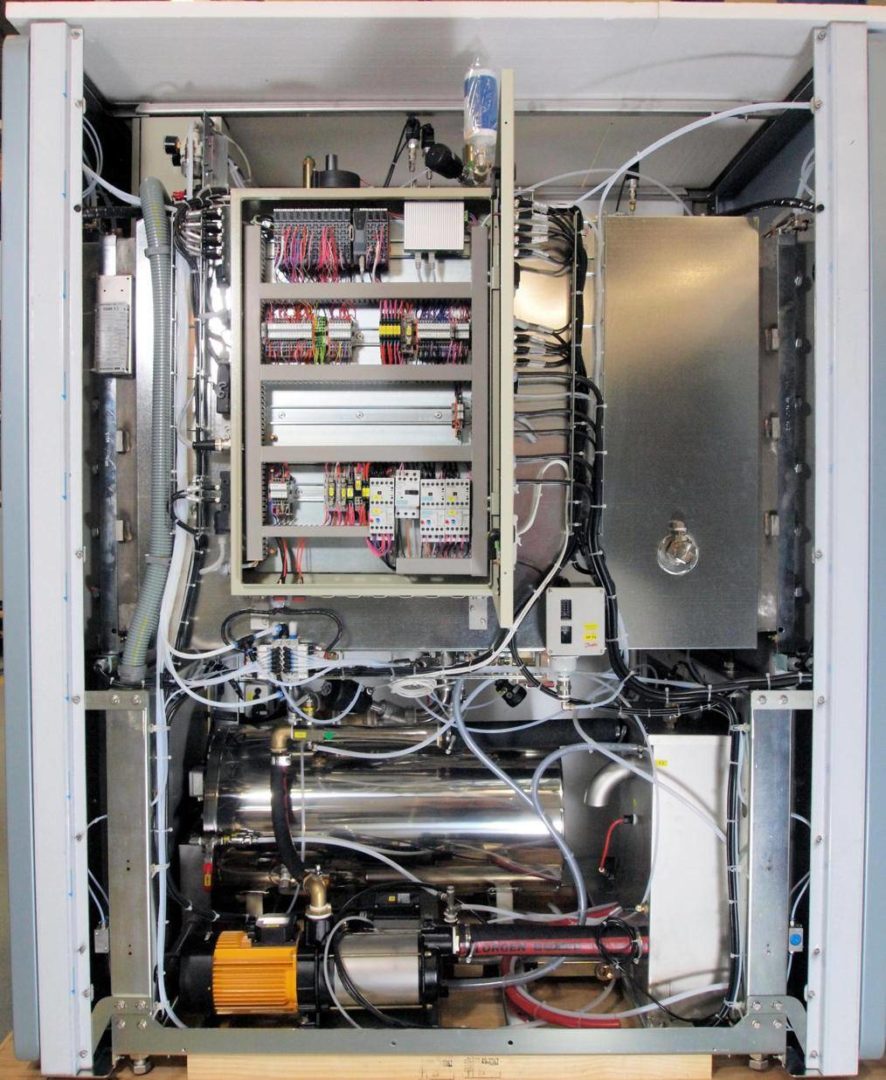

2014-03-25: A look Inside of an advanced computer controlled sterilizer.

Based on the concept that human actions are not reproducible and thus that only automatic autoclaves can provide validated processes, it became a requirement that processes for autoclaves are automatic. With the current technology this implies that autoclaves are microprocessor controlled. This results in equipment with a large quantity of high-tech components with a complex control mechanism. An example: In modern standard autoclaves the operation of a valve for steam supply requires a multitude of components: the microprocessor with its software; a relay; an electric valve controlling pressurized air; and the final pneumatic valve that controls the actual supply of steam. Thus there is a chain of multiple components for a single function with each component increasing the machine’s complexity and increasing the risk of breakdowns.

2011-10-04 Bungudu Hospital, Nigeria. In many situations a manual sterilizer is more appropriate and reliable than the latest high-tech autoclave that meets all standards

In many health facilities in developing countries, the use of complex automatic sterilizers as required by the current international standards are not feasible. For many facilities they drain the already very tight hospital budget in many cases hospitals have to resort to very basic, unsafe poor performing manual sterilizers.

For this market, more robust, well performing autoclaves are required, based on manual control and without the need of complex electronic control and related components. By allowing manual control of a sterilizer a drastic reduction of complexity and number of components can be accomplished and resulting in a more reliable essential sterile supply in the target health facilities.

Allowing manual control in the context of validation would require approval of the authorities related to the publication of the standards. It is therefore is recommended to open a debate on this issue with the relevant organizations such as CEN/ISO, WHO and possible other stakeholders. Acceptance of manual control by such respected organizations will be crucial for the commercial success of any approved sterilizer suitable for the target market.

The target market for the sterilizer would at least be all low income countries. However large regions of middle income countries, the socio economic situation also does not qualify for a reliable operating of advanced equipment. Thus the market for such sterilizers would include a major part of the worlds’ countries; which are home to a major part of the world population!

For any piece of equipment, in the context of this article a sterilizer, to provide its intended function throughout its lifespan, it should meet the following requirements

For a sterilizer two fundamental performance requirements can be identified

In any health facility sterile materials are used; a part of them may be single use/disposable; a large number of items are reusable and must be cleaned, packed and resterilized after each use. In a typical hospital reusable sterile materials are used in the operating theatre, delivery room and treatment rooms. These items are to be reprocessed in the Central sterilization department of the hospital:

For a steam sterilizer to render sterile products for use in a hospital environment, the process has the following phases

Given the socio-economic context of the target countries, one of the major requirements would be that it should be possible to use manually-operated sterilizers. Automatic control can be an option, but manual control should remain possible.

It therefore was essential to get scientific evidence that autoclaves that are manually operated can actually result in sterile goods that meet the set standards for sterility and dryness. That is why already in 1999, a research programme was implemented, in collaboration of the medical engineering department of a college on technology (Hogeschool Enschede, (NL) and the Dutch Institute for Public Health and the Environment RIVM [1]. The research took place in one of the laboratories of the RIVM. All procedures regarding the performance testing of the sterilizer were done based on the prescribed performance test methods as formulated in the respective standard for such studies (EN285). During the study two types of manually operated sterilizers, at the time common in district hospitals in developing countries were tested. Its most important conclusions.

Objective for this part of the research was to drastically reduce operator errors by reducing the number of controls/valves to be operated. In the conventional manually operated autoclaves on the market, each individual valve needs to be operated separately. Valves are at several locations on the machine. It thus requires operating multiple valves; usually 4 valves in the correct sequence and the correct moment. In several situations 2 valves need to be operated simultaneously. This method of operation requires a strict protocol and very much dedication of the staff. It thus is prone for operating mistakes. Therefore a solution was searched for by single-knob mechanical control of all valves. The research was done in collaboration with the Technical University in Eindhoven, The Netherlands in the period of 1999 until 2004. Several mechanisms were tested. However control by a camshaft system with multiple camdisks proved to be the most efficient, flexible, user friendly and cost-effective solution. It is a technology that has been used in autoclaves in the 1960’s and 70’s already but was abandoned when electronic control systems took over.

Right: The camshaft controller with its 4 valves. After a stepping the handle through its distinct 12 positions, the full sterilization cycle is completed.On the right hand side the air-cooled condenser for creating the vacuum for dryingRight: The camshaft controller with its 4 valves. After a stepping the handle through its distinct 12 positions, the full sterilization cycle is completed.

On the right hand side the air-cooled condenser for creating the vacuum for drying

|

|

| Second generation prototype of the autoclave as installed in a district hospital in Eikwe, Ghana. 2008-06-09 | The camshaft controller with its 4 valves. After a stepping the handle through its distinct 12 positions, the full sterilization cycle is completed. On the right hand side the air-cooled condenser for creating the vacuum for drying. 2007-11-16 |

The camshaft controller has a number of advantages:

5 prototypes of several generations were built and field tested in 3 countries in Africa (Ghana, Central African Republic, Zimbabwe). They are jacketed sterilizers, equipped with the camdisk controller and an air-cooled condenser as vacuum system. The first prototype was installed in 2005 has been running for 8 years without repair on the control system. The next phase is to find manufacturers in order to scale up production and finally come to an adequate commercially available autoclave that the health sector in many countries is waiting for.

The requirements of current standards have resulted in advanced medical equipment requiring the infrastructure and budget of an industrialized nation. There however is a dire need of equipment that meets the harsh local socio-economic background of many developing countries. A major cause of this situation is the lack of adequate standards and guidelines which all stakeholders involved in health care in the developing world are facing. It is crucial that this huge gap in the quest for quality, that standards organizations are committed themselves to, will be filled in. A gap that now causes sterilizers that meet all standards, and that finally (may) reach their destination in a remote hospital, may never run a single cycle. Through research it has been demonstrated that adequate sterilization can be performed in manually controlled sterilizers. Also by eliminating the electric waterring pump the complexity and water consumption can be reduced tremendously. A manually operated camshaft control system reduces operator errors considerably and thus improves reliability of the process. An add-on kit could make the unit fully automatic, opening the way to meet the requirements of the standards and still have the possibility to resort to manual control. The author is in the process of forming a working group that will address the issue of an adequate sterilizer for the rest of us.

I herewith thank all those dedicated people involved during the years of research, prototype building and field testing!

[1] B. Muis, ACP de Bruijn, A.W. Van Drongelen, J.F.M.M. Huijs. “Optimalization of the process for manually operated jacketed steam sterilizers”. Zentral Sterilization/Central Service 2002-10 (6), page 373-384

[2] WHO Department of Health Statistics and Informatics (May 15, 2013) “World Health Statistics 2013”. WHO

First published and presented during the congress on Appropriate Health Technology for Low Resource Settings 2014 – (AHT 2014), London, organized by the Institute of Engineering and Technology, UK. www.theiet.org/aht2014

Jan Huijs is the owner of HEART Consultancy, based in the Netherlands. After working as a medical equipment engineer in Ghana, Africa for 7 years in the 1980’s he started HEART Consultancy, a consulting agency focusing on sterilization of medical supplies and asset management for health facilities, focusing on the health services in the developing world. He presents training for users as well as technicians on sterilization of medical supplies in mainly developing countries since 1997. He is author of the book “Sterilization of medical supplies by steam”, which has been translated into 8 languages. He has been doing research on sterilization of medical supplies in remote areas.

Jan Huijs is the owner of HEART Consultancy, based in the Netherlands. After working as a medical equipment engineer in Ghana, Africa for 7 years in the 1980’s he started HEART Consultancy, a consulting agency focusing on sterilization of medical supplies and asset management for health facilities, focusing on the health services in the developing world. He presents training for users as well as technicians on sterilization of medical supplies in mainly developing countries since 1997. He is author of the book “Sterilization of medical supplies by steam”, which has been translated into 8 languages. He has been doing research on sterilization of medical supplies in remote areas.

Since 2014 Jan is honorary member of SVN; Sterilisatie Vereniging Nederland, (Dutch Sterilization Association).

Upgrading of sterile supply department.

Upgrading of sterile supply department.

Implementation partner: Medical Mission Institute Wuerzburg, Germany

Local partner: St. Josephs Hospital, Monrovia, Liberia

Implementation: 2014-2015

Activities

The project was implemented during the time of the Ebola epidemic

For a brief project description click here